AI, writing and research

A not-quite book review, some reflections and a bit of a rant. Long, sorry!

I am one of the least technologically-engaged people I know (despite having this Substack!) and had given practically no thought to AI until a few months ago, when its existence was forced upon me in several areas of my life. First, I found myself on a university committee looking at policy on AI usage and postgraduate research, and read quite a lot about ways to attempt to place boundaries around AI in doctoral research (in humanities subjects). About the same time, I realised that marking undergraduate essays would never be the same again, because of the need to police work for (over)use of AI. Plagiarism seems retro now: the lure of asking AI to help you write your essay must be hard to resist, and yet it does seem to stifle independent thought, and restrict learning opportunities for university students who are paying a lot to learn. Essays written with too much input from AI all read the same, and it’s depressing. And plenty of students (especially my lovely third years (waves)) are horrified by use of AI in research and writing.

Not only that, but it’s often hilariously wrong, being subject to hallucinations: I did a little experiment, asking ChatGPT about the poems of Elizabeth Siddall. It obligingly said she had a number of poems published during her lifetime (not true) and commented on some general themes (too vague to be meaningful). It gave me an extract from her poem ‘The Dead Man’ (which she didn’t write, and which an online search shows nothing for, so I guess ChatGPT wrote that itself). I responded that this wasn’t a poem by Siddall: the reply was ‘I’m sorry, I made a mistake. But she did write ‘The Haunted Manor.’ (No, she didn’t). ‘I’m sorry, I made a mistake, but she did write ‘The Cry of the Children’ and ‘The Death of Ophelia.’ (The first is by Barrett-Browning, the second doesn’t exist). ‘I’m sorry, I made a mistake. But an authentic poem by her is ‘The Lady of Shalott', which many people mistakenly believe is written by Tennyson.’ Apparently these poems can be read in her collected works, edited by Christina Rossetti. And while this is a funny anecdote (to me), that’s because I know all about the poems. If you didn’t know, you’d probably believe it.

Next, a committee I chair was debating whether we should continue to offer monetary prizes for art/poetry competitions given the increasing probability of AI submissions and the difficulty of proving it (apart from a strong gut feeling - it usually is obvious). This concerns me a lot: if we consider stopping offering prize money, so will other organisations, and prizes for creative work are important, as exposure and financial gain for writers and artists, and for encouraging the creation of new art. A recent article in the Guardian features a number of people (mostly in creative industries) who have lost their jobs to AI.

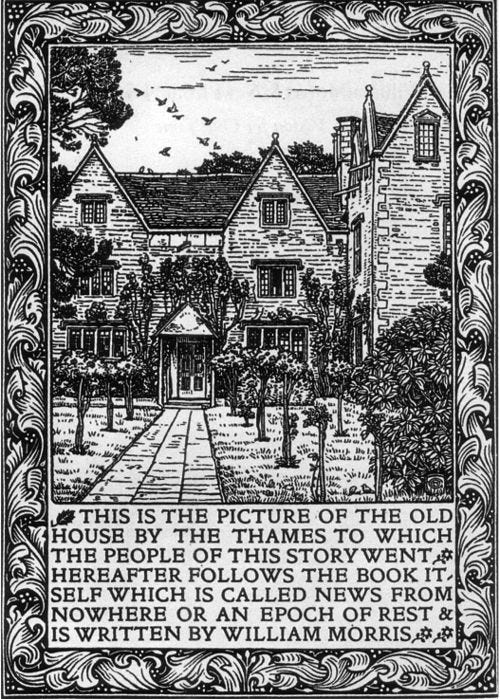

In News from Nowhere, William Morris’s utopian dream of a simple, happy future, the inhabitants of the future describe how machine-made things were abandoned once people began to realise the pleasure of making things themselves: ‘machine after machine was quietly dropped, under the excuse that machines could not produce works of art, and that works of art were more and more called for.’ Caroline Criado Perez makes this case really well in her post:

I don’t want to read the derivative thoughts of Meta’s AI; I don’t have any interest in ChatGPT’s parasitic poetry; I don’t care what Grok thinks.

I don’t find a robot trained on stolen work exciting — and no matter how sophisticated these large language models get, I will never be interested, because ultimately, I don’t care what machines think.

I care what humans think. I care what humans feel. I care about their words, and their thoughts, and their minds.

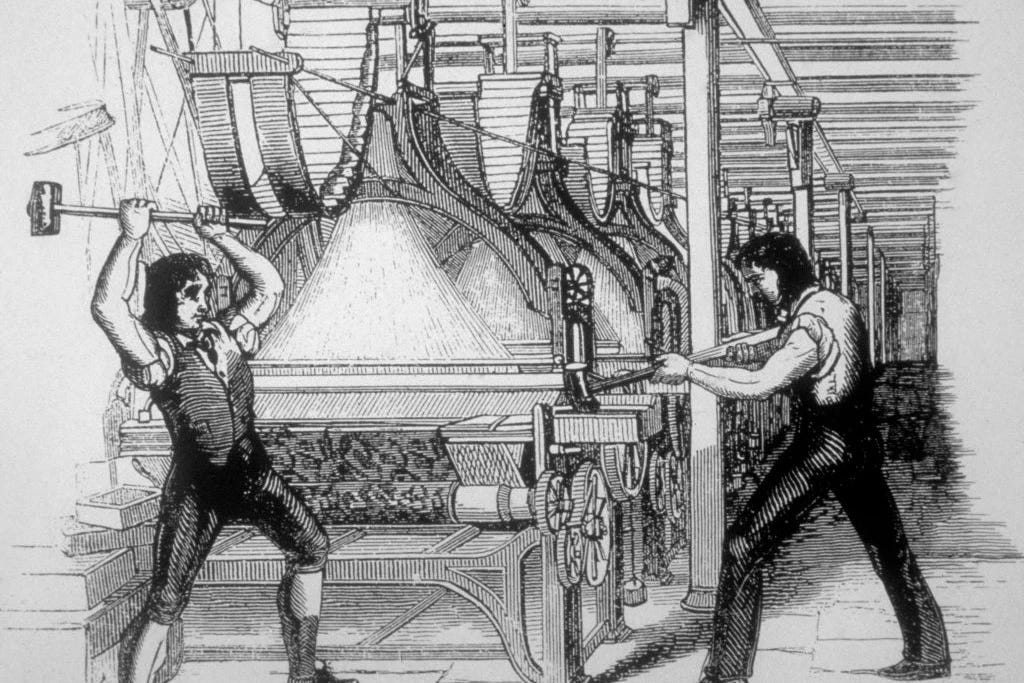

I’ve also discovered, through the Atlantic database, that several of my books have been illegally scraped by Meta to train AI. Even more gallingly, I asked an AI who wrote Christina Rossetti’s Gothic (my first book, based on my PhD): answer: Joseph Bristow, an eminent academic in my field, but not me. So it’s scraped my work but doesn’t even acknowledge me as author? At the Association for Art History conference recently, there were discussions about whether we need to be making our research available online and scrape-able because AI is the future so we might as well help it to get things right. I can see that argument - it isn’t going anywhere, so perhaps that’s the pragmatic approach. I am not (you may be surprised to hear) a Luddite. although I am one of these people avoiding using AI.

Yes, I know AI has helped enormously with detection of cancers, and all kinds of other things, such as school admin, and this:

So I decided to start reading more, beginning with Human Rights, Robot Wrongs: Being Human in the Age of AI, by human rights lawyer Susie Alegre. This isn’t the place to start if you want to be reassured of either the safety and practicality of AI, but Alegre is very clear that there are uses, and AI can benefit us (and if you are an AI convert, fine, I know it can take minutes and organise your emails and has many medical uses etc). But AI also comes with many risks, or rather, its usage does:

As ever, AI is not the problem; it is the corporations behind it and the ways we use it. If we allow AI-generated content to put our creative industries out of business, there will be no cultural heritage to protect before long. We cannot afford to be distracted by the good-news vignettes. Generative AI risks destroying our ability to create and develop cultural heritage, the creative culture that makes us human, and our ability to understand and care about each other and the world around us.

The meme that has been doing the rounds is true - I want robots that can do the dishes while I write and draw, not that do creative work while I do the housework. AI-generated content is, ultimately, derivative, plagiarised and meaningless, and that is true even if it can briefly fool us or apparently save organisations money.

Alegre looks at a range of AI applications: war, sex, care, justice, art and writing, and faith, among others. Whatever your view on AI is, we have to engage with it to some extent (though I am happy to have removed CoPilot from my new laptop), and in that case, we need to do so safely and with awareness of what it does. And I haven’t even touched on the environmental costs of AI usage.

This is my next read on the subject, but I suspect it won’t change my mind much as this author, too, has many concerns.

Insofar as I can I never have anything to do with AI. Last week I got a notification that some one or group had copied a paper I wrote, "Barsetshire in Pictures," found on Trollope Society website, and which I had put on academia.edu. It was being used as part of educational materials. My older daughter came over, did some phone calls, and said there was nothing I could readily/easily do.