This beautifully produced book, with a large number of images, provides a full account of the contribution of Elizabeth Siddall (here referred to as Elizabeth Rossetti, for reasons that are clearly explained) to the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Despite the popularity of Siddall as a subject for research as well as speculation, this book has plenty of new research and interpretation to add to what is already extant, and will become the standard work on Siddall, in my opinion.

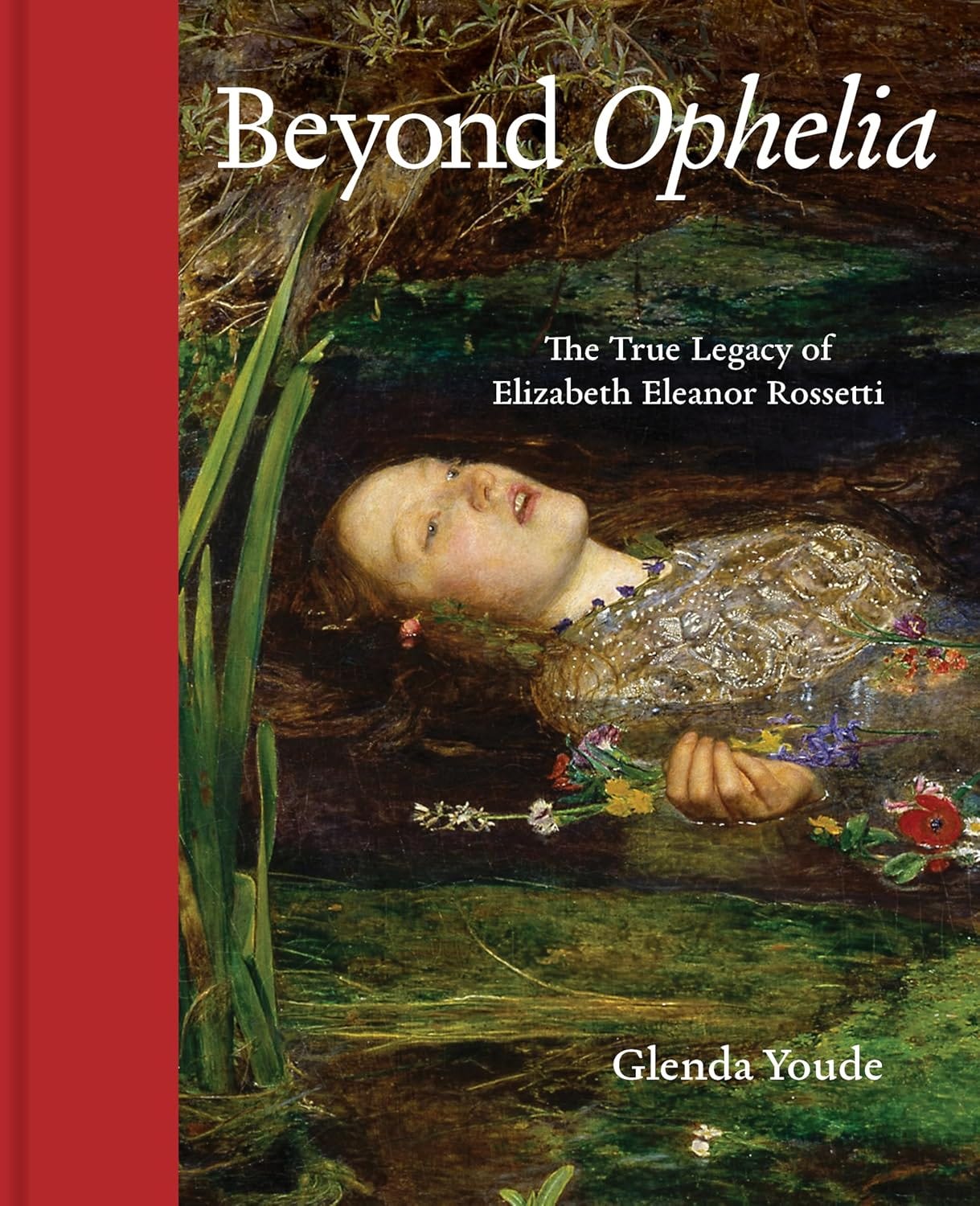

Youde opens by tackling what she calls ‘the Ophelia problem’: the mythology that has developed around Siddall’s life which obscures her reality as an artist and poet as well as a model and wife of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. From the bathtub which went cold to the firelit exhumation, the book begins by describing the myths, and then unpicking them, using solid research to present an alternative narrative of Siddall’s life which is more closely based in reality – and, as the book demonstrates, the reality is every bit as compelling as the myths.

This untangling of the myth from the reality proceeds with a discussion of the monographs which have looked seriously at Siddall’s work, as well as considering the exhibitions in which her work has appeared, from her lifetime onwards. The scene thus set, Youde thoroughly explores the complex history of the photographic record created by Rossetti of his late wife’s works. It’s particularly interesting to think about the potential significance of the portfolio, both as a record of her work (thus establishing her for posterity as an artist) and also the ‘strong possibility that Gabriel kept a copy of the portfolio for himself for use a source book. Elizabeth’s ideas, documented in the photographic portfolios, have permeated the work of other members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle.’ (p. 71)

Subsequent to this significant scene-setting, the book offers some very detailed and sound analysis of some of Siddall’s works. The observations are original and scholarly, but it’s worth pointing out here that this is also a very readable and accessible book. Works carefully analysed in the book include ‘The Lady of Shalott’, above, Siddall’s 1853-4 self-portrait, ‘Pippa Passes’, ‘Lady Clare’, below, ‘The Lass of Lochroyan’ and many others.

The analyses pay particular attention to ‘looking’, which Youde references to Deborah Cherry’s Painting Women, considering looking as a way of empowering women is explored. Youde contends that

Much has been written about Elizabeth’s choices reflecting her transition from model (being looked at) to artist (being able to look). Yet there is more to Elizabeth’s depiction of women than simply the act of looking. It is the reason they are looking that is critical to understanding her oeuvre. (p. 104)

I think this is absolutely right, and am excited by the possibilities for exploring her work (including her poetry) in this light.

Another stimulating thread here is Youde’s argument that Rossetti, and potentially other Pre-Raphaelites, were inspired by Siddall’s work, a pleasant shift from earlier arguments that her work was derivative. Quoting Liz Prettejohn’s argument that ‘the participation of women … shaped the collaborative practices of the movement’, she argues for an artistic partnership between Rossetti and Siddall. There is considerable analysis of Siddall’s work alongside Rossetti’s, examining shared approaches and themes, a tactic which is long overdue.

The final section of the book, focusing on Siddall’s legacy, takes into account Siddall’s role as a ‘muse’ to Rossetti, but does not confine this to her modelling; Youde describes what she calls ‘the Lady Clare effect’, in which her beautiful watercolour of 1854-7 inspired other Pre-Raphaelite artists with its unconventionally depicted heroine. From Lady Clare’s awkward angle of the neck, as though bowed down by a mass of hair, many other works by Rossetti are traced, and there are other striking examples provided and illustrated here of Rossetti and others in the Pre-Raphaelite circle taking inspiration from Siddall’s work.

The book concludes that ‘Elizabeth has left us a valuable legacy – concealed within the work of her male counterparts’ (p. 191). We must, Youde urges, forget the myths and stories, and look instead at the artist, as she deserves.

A longer version of this review will appear in the Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society later in 2025.