I have developed a lovely middle-aged habit of walking round my garden taking photos of flowers in the morning. And since my head is also full of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, the two go together for me. The Pre-Raphaelites, as you probably know, painted nature in photographic detail, not only for the sake of realism but also for symbolic purposes. It seems to me that few of them use flowers with such a close association to character as Sandys does, consistently, throughout her oeuvre.

So, on to the flowers. Firstly, honeysuckle.

Honeysuckle has all kinds of historical and folkloric associations, including with fidelity and lasting passion, but also purity. Most interestingly, it’s also associated with the Virgin Mary, a link first apparent in 1873, according to the OED, ie two years before the date of Sandys’ painting. It seems unlikely that this medieval lady is intended to be Mary, but various sources suggest that these Marian associations were present for centuries earlier than this. However, I’d like to suggest a different link.

We know that Sandys often took literary, mythological or historical characters for her subjects, and that she researched them carefully, so I have a suggestion: Iseult (from the Arthurian story of Tristan and Iseult. In her lay ‘Chevrefoil’, Marie de France uses the metaphor of a hazel tree and a honeysuckle to represent the love of the couple. The two plants were assumed to be inseparable once bound together, and would die if separated – and Tristan and Yseult die of a broken heart on the same day.

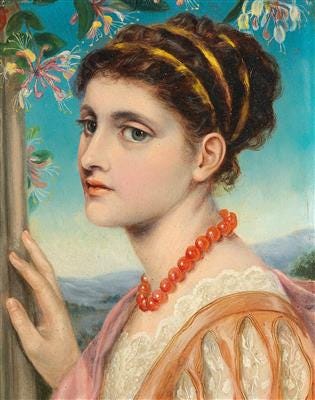

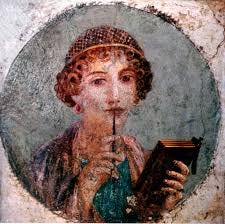

The next painting is Daydreaming, c. 1867. Here there is a young woman, with a curious gold Ancient Greek style binding in her hair and a coral necklace which appears in several of Emma and Fred Sandys’ works, apparently in a reverie (a popular state for young women in the nineteenth century if paintings are anything to go by). The honeysuckle appears in the top left, with misty hills behind her. Again, it probably represents fidelity and/or passion, so my wild surmise here (I’m having fun with this, even if I’m completely wrong!) is that this could be Sappho. My research suggests that paintings of Sappho (quite a popular subject in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when Sappho wasn’t always seen as Sapphic) often feature misty hills, which I think might prefigure her Leucadian leap (when she flung herself off a cliff due to her unrequited love, apparently).

The gold bands and pose of reverie are also common features of other paintings of Sappho. Sappho appears in the poems of both Letitia Landon and Felicia Hemans, which it is probable Sandys would have knowledge of. Landon’s ‘Sappho’s Song’ describes a scene which could be an inspiration for Sandys’ painting:

And then the beautiful, the grand,

The glorious of my native land,

In every flower that threw its veil

Aside, when wooed by the spring gale;

In every vineyard, where the sun,

His task of summer ripening done…

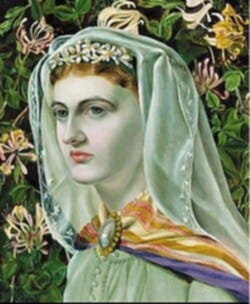

A Lady Holding a Rose (c. 1870-1873) contains both a pale rose and honeysuckle. I’ve previously speculated that that this woman might be Guinevere, with Camelot in the background, pondering her difficult situation as she is torn between her love for her husband Arthur (represented by the honeysuckle, meaning loyalty) and Lancelot, indicated by the roses, which stand for passion. To the left there are also irises, for courage, and also a symbol of royalty.

However, further investigation suggests another possibility for this painting. Rosamund Clifford, the lover of King Henry II, was a popular subject for Pre-Raphaelite paintings, including Fair Rosamund and Queen Eleanor by Edward Burne-Jones (1862), Fair Rosamund by Rossetti (1861), Fair Rosamund by Arthur Hughes (1854) and Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund by Evelyn De Morgan (1901-2). All of these paintings have interpreted the “Fair” as not only beautiful but with light-coloured, abundant hair, and with vaguely medieval dress, as we see in the slashed sleeves of the figure in Sandys’ painting; of course, there is also the rose held by the figure, and “Rosamund” means “Rose of the world” in its Latin origins. Moreover, it is known that Sandys exhibited a crayon drawing of “Fair Rosamund” in 1874 at the Society of Women Artists, a work which is no longer extant but which may have been made earlier than the date exhibited as a preliminary drawing; the oil might have been sold and thus not available for exhibiting.

Finally, my beautiful sunset roses take me to Sandys’ last painting, the unoriginally titled ‘Study of a Head’, on which is written ‘The Last Study of the Late Miss Sandys, 1877’. No particular theories from me here, but while the internet assures me that these colour roses indicate strong passion, there is, to me, something poignant about the parallel between these roses which reflect the colours of the sky before night falls and the unfinished painting which she worked on until her sudden illness and rapid death.