Rembrandt etchings

Looking very closely at Rembrandt at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Until June 1st, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery has an exhibition, Rembrandt: Masterpieces in Black and White, with a number of works on tour from the Rembrandt House Museum in the Netherlands, alongside some of BMAG’s own Rembrandts and the work of other, local printmakers. Although we may think of Rembrandt as primarily a painter, of wonderful gloomy scenes lit with astonishing light effects, this exhibition demonstrates his skills in etching and printmaking, and I found it an absolute joy. The works are very small in most cases, and in order to make good use of the magnifying glasses helpfully provided, it’s advisable to try to attend at a quiet time, as I did, to be able to get a really good look at the works – and they repay careful looking.

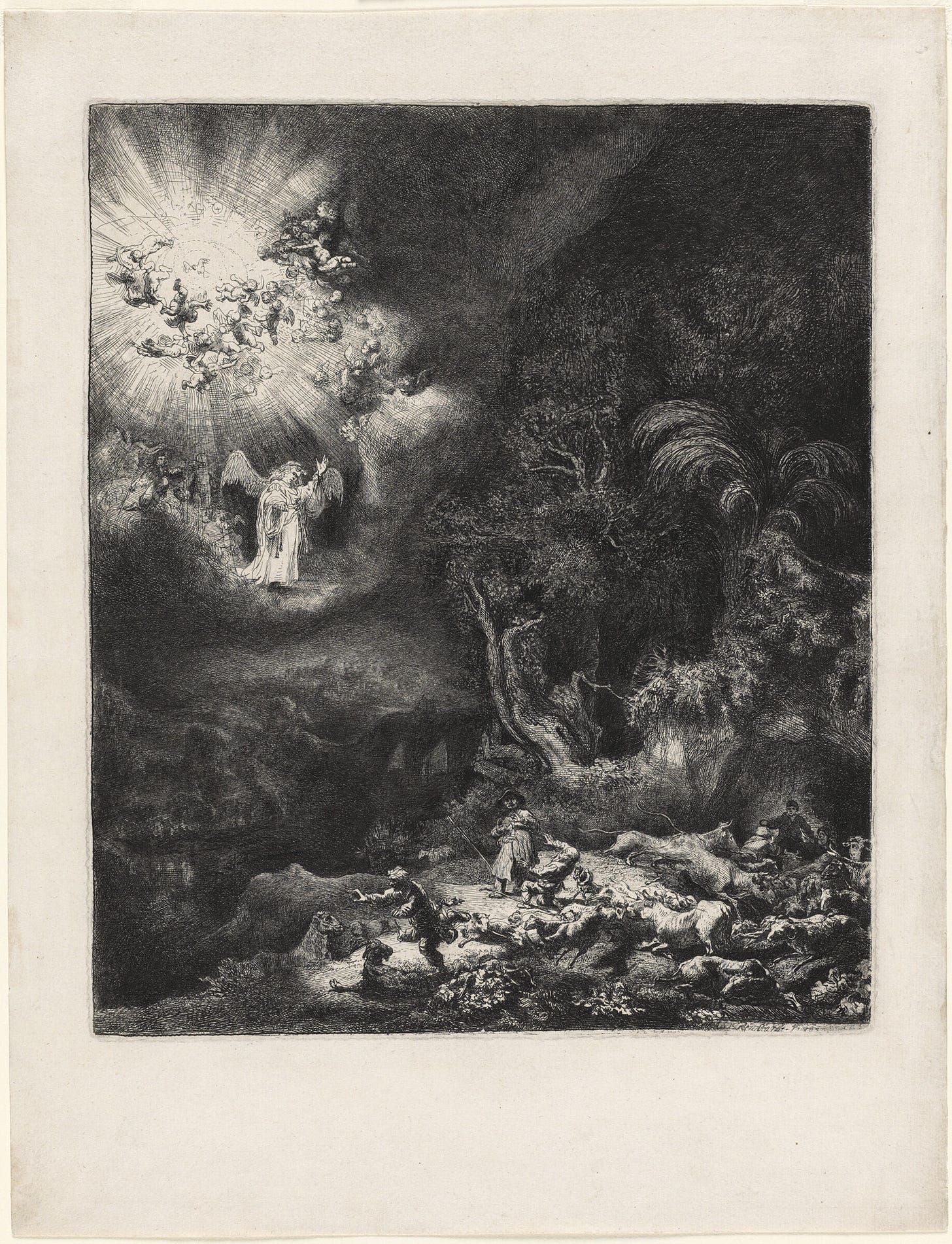

The exhibition highlights several particular approaches to the works on display: his experimentation with both the medium and the form of the work; his use of light and dark; and his remarkable abilities as a storyteller. All of these are very striking when looking at his work, and the exhibition is themed to emphasise these – From Life, Light and Dark, Shaping a Character, Landscapes, Techniques, Stories. The last of these is perhaps the one I focused on most, because in these tiny etchings which are filled with life and movement it feels as though one is looking at the scenes as Rembrandt saw them – he seems to offer direct representations with a great sense of immediacy, from his self-portraits to his street scenes. There seems to be no filtering (of course there was filtering, but to feel there isn’t is a source of power in the works) as he represents poor people about their business, such as the ‘Blind Fiddler’ with his dog (1631), above, or the wonderful interiors.

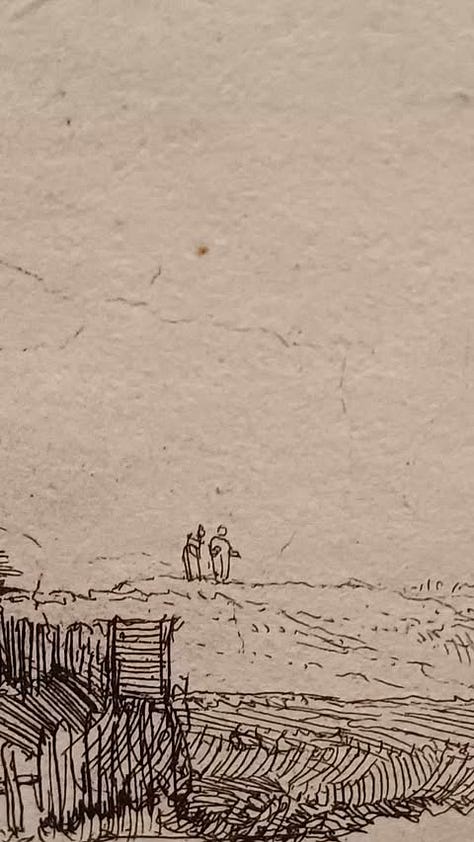

It really struck me the enormous attention to detail: in ‘Woman Sitting Half-Dressed by a Stove’ (1658), above, there is as much observation and detail in the chamberpot and the stove as there is in the figure and the shadows which fall around her. The images really repay close looking: from a distance, the image is perfectly clear, yet move closer and we begin to see the strokes which form the people, the places, the shadows – and then look closer still, with the magnifier, and other things appear – tiny people on the horizon, or faces peering from the darkness. I especially love the night scenes, such as ‘The Star of the Kings’ (1651), below, where the effects of light and dark both obscure and illuminate the figures, causing the viewer to peer as if in the dark themselves.

One of my favourite works here is ‘Windmill’ (1651), featuring the fantastically detailed ‘Little Stinkmill’, a tumbledown house behind it, and an empty, flat expanse of horizon behind it, which, barely visible to the naked eye, contains two people walking away. It feels like the start of a medieval fairy tale.

The section which explores technique, including a short film and information panels about etching techniques and the paper used for printing, is fascinating, especially as there are two of his etching plates – and it’s astonishing to me that what is barely discernible on the plate (such as the tiny shadings of light and dark) come across so crisply in the final works.

You can’t whizz round this exhibition, or you’d miss the real beauty of the close looking. ‘St Francis beneath a Tree Praying’ (1651) is packed with tiny, meaningful details such as Christ on the cross in the shadow of the tree. Other works, especially some of the biblical scenes, seem to appeal to all the senses with their life and movement and evocation of sound and smell. It struck me that all of these works require something of us – attention, time, careful scrutiny, but also a will to understand the mind of the artist and the world he lived in. Look at ‘Angel Appearing to Shepherds’ and see if you feel moved by the tiny tumbling cherubs, and feel the awe of the shepherds, too. The size of the works is small enough to make us move closer, and yet the texture is deep enough to allow us to fall into their worlds.

There is an online booklet for the exhibition which tells you more about Rembrandt, his work and his etchings, here.

Thank you, especially for going to the trouble of reprinting the images. Ellen