The Merry Maidens, at Boleigh, near Lamorna, seems to have the most entrenched mythology of any stone circles in Cornwall, albeit a common one with its moralising petrifaction trope. A similar myth is appended to Boscawen-un, the Nine Maidens at Boskednan, and the Hurlers on Bodmin Moor. Petrification is a common story for the genesis of stone circles, and has its roots in many folk and fairy tales, classical mythology and the Bible.

Other myths have been extant, however – in 1861 James Halliwell says that the stone circles of Cornwall are popularly considered to be monuments of giants. William Borlase writes in 1754 that the holed stone and other stones around the circle “might be employ’d for the Sacrifice, and to prepare, kill, examine and burn the Victim’. He sticks firmly to his Druid mythology, suggesting that where there is more than one circle of stones (as there was here at one time), the small circle was used by the inferior Druid priests. Borlase states that the circles of Cornwall are called ‘Dawns men’, meaning the Stone Dance, because they are a space for dancing.

Robert Hunt, in his Popular Romances of the West Country, in 1903, tells the story of the Merry Maidens:

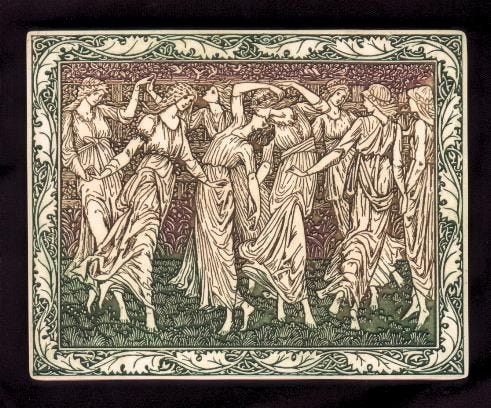

One Sabbath evening some of the thoughtless maidens of the neighbouring village, instead of attending vespers, strayed into the fields, and two evil spirits, assuming the guise of pipers, began to play some dance tunes. The young people yielded to the temptation; and, forgetting the holy day, commenced dancing. The excitement increased with the exercise, and soon the music and the dance became extremely wild; when, lo a flash of lightning from the clear sky transfixed them all, the tempters and the tempted, and there in stone they stand.

The Pipers stand a little way off from the circle, and in other versions of the myth they are running away to escape the curse of petrifaction. Julian Cope suggests the circle are revellers at a Saturday night party that went on into the Sabbath. Richard Hayman tells the story slightly differently, suggesting that the women were on their way to church across the fields when Satan and his fallen angels, disguised as musicians, tempted them to dance, leading to their petrification for disobedience. The echoes of the fall of Eve in Eden are clear here.

Claude Berry’s 1949 guide to Cornwall comments on the petrifaction legend, saying that

The fiction seems innocent enough to me, and I think it is just possible that the legend of the dancers was devised by eminently practical Cornish matrons, concerned less with the moral turpitude of maidens who dance on Sundays than with the ill effects such outdoor frivolities might have upon their daughters’ best frocks.

Berry lightly dismisses the idea that the myth might have begun as a way to control girls’ behaviour, but I don’t agree. The tales of the dancing girls (or, in some cases, men playing at hurling, or a mixed wedding party) turned to stone for what is perceived as immoral behaviour seem to have begun some time in the seventeenth century, as far as sources indicate. It has been suggested – and it seems probable to me – that these tales originated as a way of marking these sites as dangerous, and off limits. The concept that the stones were once human adds a creepiness to them which might well deter many people. Moreover, it removes the connotations of pagan worship which had attached to the stone circles, replacing it with righteous punishment. And finally, it serves as a warning to those who misbehave: divine retribution will overtake you eventually. Robert Hunt tells us that ‘These stones are everlasting marks of the Divine displeasure, being maidens or men, who were changed into stone for some wicked profanation of the Sabbath-day. These monuments of impiety are scattered over the county’. Richard Hayman suggests that these stories were told as exemplum, or moral warnings, since the 16th century.

It's interesting, though, that the majority of stories of petrifaction involve girls or women. If we accept that these stories may have originated as Christian warnings against what was perceived as immoral behaviour, there is an interesting precedent here. In Genesis 19, when God destroys the wicked city of Sodom, the angels tell Lot, his wife and daughters not to look back at the burning city. Lot’s wife looks back, and is thus disobedient and lacking in faith, and is turned into a pillar of salt. Modern views on this are that we should not judge Lot’s wife too harshly, leaving behind her home, but her Old Testament punishment is a kind of petrifaction, and in the New Testament Luke exhorts us to remember the example that was made of her. Jewish texts make more of Lot’s wife, even giving her a name, though here she is figured as a gossip as well as disobedient. The Apocrypha mentions her as "a pillar of salt standing as a monument to an unbelieving soul."

There is a strong sense here, then, that the dancing girls myths are a way of policing women’s behaviour. Dancing round stone circles at night was obviously not respectable, moral behaviour for women. And yet, the myth has stuck, and has been transformed in some ways, as retellings seem to focus on girls who can dance perpetually – not to the death, like Karen in The Red Shoes, but eternally free to dance together.

Halliwell remains convinced that the stones are all sepulchral in original purpose, that is to say, grave markers, although human remains are rarely found at these sites. He does, however, mention Athelstan’s victory, and this leads me to another, earlier legend.

Aethelstan, considered the first King of England, fought various battles, including against the Scottish and English leaders who did not wish to be ruled by the Anglo-Saxon King. Cornwall also resisted, and in 936 a Cornish (or Welsh) leader, Howel, and his army supported by the Danes fought Aethelstan at Boleigh, sometimes translated as ‘the field of slaughter’. The Saxons then erected the circle to mark their victory, and the Pipers represent the two kings, Howel and Aethelstan, in peace talks away from the crowd. Apparently the stream nearby ran with blood after the battle, and armour was recovered in nearby fields for centuries to come. The year is consistent with when Aethelstan was increasing his rule, and is around the time when he routed the Cornish from Devon, but of course the stones are considerably older than this.

Aubrey Burl hints at another, older story. ‘In 1201 it was recorded as Rosmoderet, later Rosmodress, a reference to the heath on which the land was built, which translates as ‘Mordred’s rough land’…’ There is, of course, only one Mordred, the treacherous nephew of King Arthur, though references to him tend to occur further up the county. But, it seems, all ancient stones lead me back to King Arthur eventually, so I did a bit more digging.

There was a King of Wales, Brittany and Cornwall who apparently died in battle in 936, called Hywel Dda, or Howell the Good. He might actually have been real. Howel is mentioned by the notorious writer of fictional history, Geoffrey of Monmouth, some time in the 12th century, where he is placed as a contemporary and court acquaintance of Uther Pendragon (and a 2017 study of Celtic sources suggests that Geoffrey’s accounts are in many cases upheld by archaeological fact and written records, interestingly). The 13th century Prose Lancelot and Tristan tales also include Howel. So the links to Arthurian myth increase; Mordred wasn’t a common name, so the implication is that earlier stories of the stones at Boleigh, judging by the name of Rosmodoret recorded in 1201, related to the Mordred of Arthurian tales, perhaps through connection with Howel.

So much of this is tenuous, based on inference and supposition, but such tales are an insight into how human nature puts stories at the heart of things, to interpret the world around us.

So fascinating! Many thanks for this post Serena!