Vanessa Bell: A World of Form and Colour

I have always been drawn to Vanessa Bell, ever since I discovered her paintings at the Courtauld Institute when I was an undergraduate, so I treated myself to a day out to visit the exhibition at the Milton Keynes Gallery, ‘Vanessa Bell: A World of Form and Colour’. It was well worth the journey - it provided a wonderful retrospective of Bell's work and gave me a lot to ponder.

The sensuous mind within preoccupied

By lucid vision of form and colour and space,

The careful hand and eye, and where resides

An intellectual landscape’s living faceJulian Bell's poem about his mother

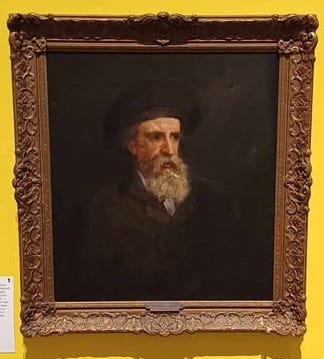

The first room contained mostly portraits, moving from the Victorian-style, Tennysonian sombre portrait of her (actually Victorian) father, Leslie Stephen (1902-3), to post-Impressionist portraits of her friends. In these, even the sketchy, faceless figures with emphasis on 'form and colour' suggest movement and life wonderfully to the viewer. The contrast is wonderful, and individual to the subjects, indicating Bell's range in even her earliest works.

The exhibition contains many of her still lives, and I have always loved her odd, slightly distorted paintings of objects, often with a peculiar perspective, perhaps slanted, which has an interesting effect on the viewer (I find myself trying to straighten myself rather than the painting in order to attain the 'right' angle to view it, which makes me think about the relationship between painter, object and viewer. She has a way of painting the very thingness of things, as if you could reach out and touch them (I didn't!) despite their refusal of realism.

Then, of course, there are the actual things: so many of them and so beautiful: a fan, a desk, clothing, fabrics, bedheads, screens, book covers, produced by the Omega Workshops or by Bell for her home. There is something so apparently simple and naïve about many of these objects, and yet their beauty is in their lines, their colours and shapes and the way in which they both blend in with and stand out from the objects around them. No wonder that the 'Bloomsbury Look' is so popular: she makes the ordinary extraordinary.

To some extent, it feels as though Bell painted people as 'things', too: not in an objectifying sense but in the way way in which they - especially women, interestingly - fill the frame and become a focus as if they were an object in a landscape as much as a figure in a domestic setting. And many of her paintings are domestic and intimate, both those of Duncan Grant and others at Charleston, and those of women; as one of the exhibition labels says, her women are 'monumental' rather than fragile - as, perhaps, Bell herself was.

And though there are many paintings of men and children here, it does feel as though Bell is most interested in painting and engaging with other women. She captures the childishness of children beautifully, too. A Conversation (1913-1916) is one of my favourites of her paintings; it captures intimacy and urgent chat so well, painting women who just are.

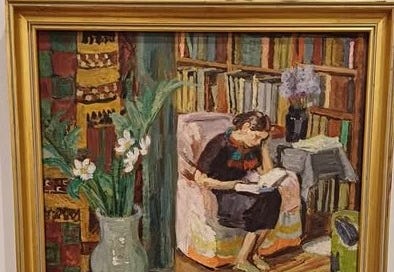

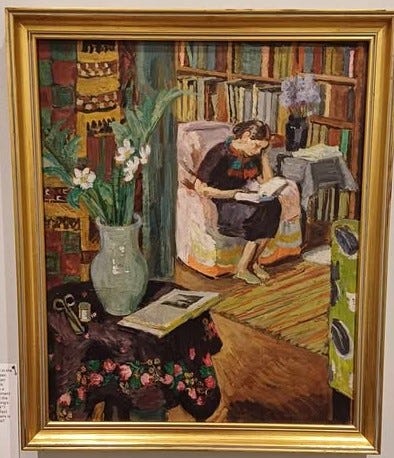

There are far too many things to comment on all of them, but the exhibition also shows how her work develops over time, becoming more naturalistic (and the labels tell us how she described or defended that during her lifetime). The range is inspiring: detailed, beautiful drawings of the kind I don't associate with the bod brushstrokes or beautiful colours of her work; stage sets for ballets (how did I not know about those?!), and the most beautiful interiors in her paintings - one of my favourites of which is Interior with Artist's Daughter (1935-6), below.

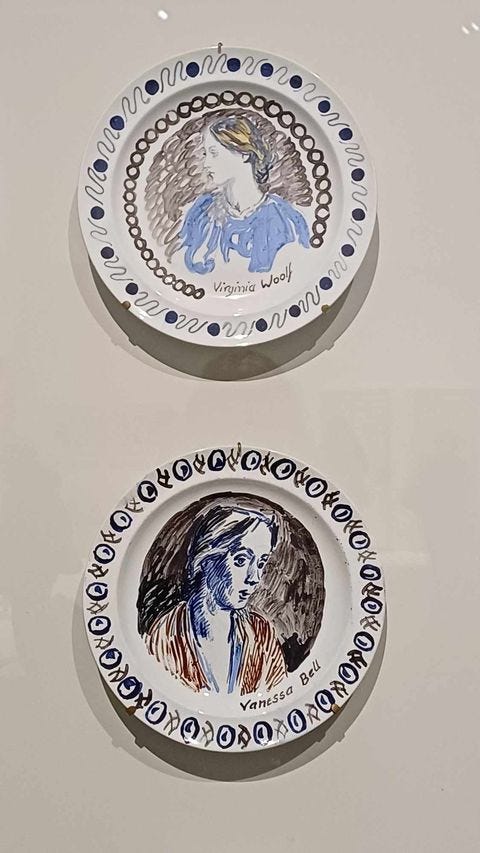

Perhaps what I was most excited to see was the Famous Women dinner service. After all, where else can you see portraits of Miss 1933, Elizabeth Siddal, Greta Garbo, Virginia Woolf and Elizabeth I (among many others) in one place?! The dinner service was commissioned by Kenneth Clarke and his wife in 1932, produced by Bell and Duncan Grant, and consisted of 50 hand-painted plates, featuring images of women divided into categories of Women of Letters, Queens, Beauties, and Dancers and Actresses.

Perhaps today we might consider this somewhat reductive, but the effect of all these faces of women is powerful, and of course the concept has had an afterlife, too, in Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party and Caryl Churchill's Top Girls. Imagine having all these women to dinner! Truly a fantasy dinner party - and what a conversation would ensue.

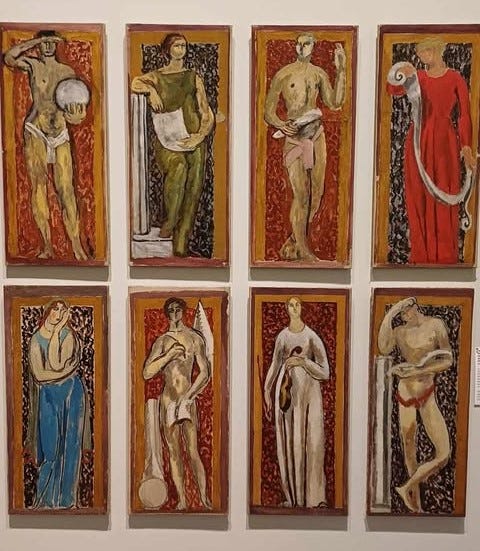

Of course I particularly love the images of Siddal and Christina Rossetti, and I found other Pre-Raphaelite links too: 'Studies for the Muses of Arts and Sciences' (1920), below, which she completed with Grant, has a definite Pre-Raph aura about it; and the label beside 'The Annunciation' points out the resonance of this subject for Bell, since their mother, Julia Jackson, modelled for the Virgin in Burne-Jones's 1879 painting of the same title. Somehow, everything I do comes back to the Pre-Raphaelites!